Australian film maker and OYUKI® ambassador Lucas Wilkinson travelled to Ecuador with a particular mission in mind. To ski somewhere most people would never think to ski and, at the same time, highlight the issue of how climate change is affecting some of the most unique skiable terrain on the planet.

Avenida De Volcanes or ‘The Avenue of Volcanoes’ in the Ecuadorian Andes ticked all the boxes. Exotic location, high altitude, volcanoes, proximity to the equator and, most importantly, a rapidly disintegrating glacier. This is the story of Lucas’s ‘last decent’…

An Adventure to the Equator

During a particularly hot February night in my native Jindabyne I had an epiphany, the first of many over the course of this story. In snow sports, everyone is always bragging about a “First Descent”. The act of being the first person to ski down a mountain, ever, in the history of the universe. Like, that’s cool and all, but what about if you were the last person to ski down a mountain? Because the climate of the planet is changing. After you skied down a mountain one last time, it melted, never to be skied again. One “Last Descent”. So, armed with this idea and a plethora of new information, I set out to make a film about skiing/snowboarding down some of the most at risk glaciers in the world. Those on the equator.

Sure, it’s easy to write it down on paper and say, “heck yeah, let’s get funding and make this film happen”. But, it’s far more real to experience it in person. To see if the problem actually exists (it does). To sort out if it’s possible to make a film in these mountains (it is….won’t be easy though). And to get a “feel” for these environments, that are so far removed from the classic winter destinations. I found a guide, Pablo Puruncajas, who comes from a long line of mountaineers. He grew up in the shadow of Chimborazo, the highest mountain in Ecuador. He was climbing these volcanoes with his father, also a mountain guide, as early as 10 years old. Pablo had guided on Denali, Mount Blanc, Renier and more. He was local and a passionate skier, an essential prerequisite for what I wanted to achieve. He was my guy.

Reaching for Cayambe (5790m)

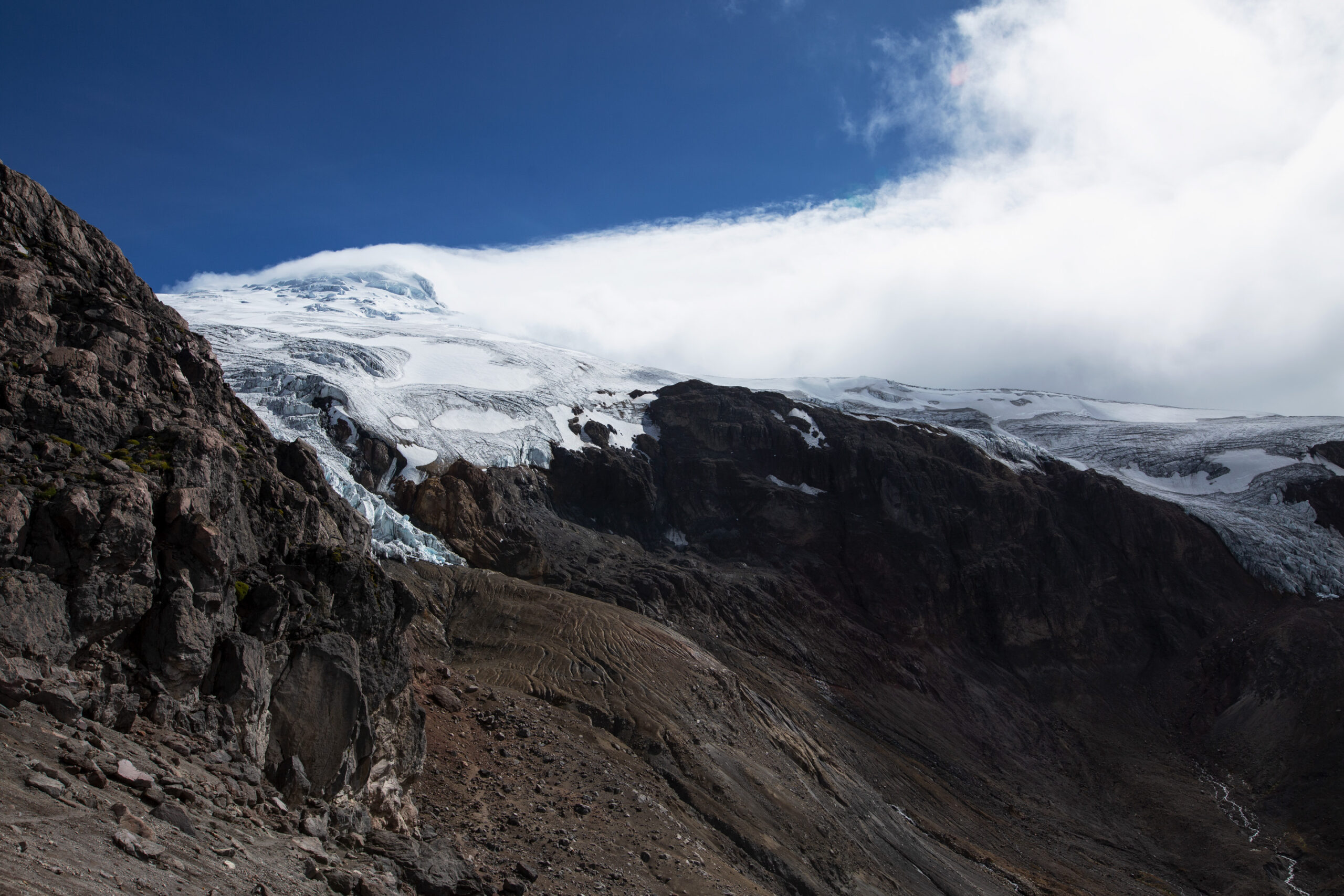

The first thing I’ll mention about big mountains, in general, is how hard everything becomes at altitude. Despite time spent at altitude trekking in Nepal, I underestimated how the most menial of tasks become a mammoth effort once you’re above 5000m, even with proper acclimatisation on some of the smaller peaks in the region. After a few acclimatisation days, and a heavy bout of “gringo guts” (debilitating food poisoning), we headed up high for our first ski tour day, to our first glacier, on Cayambe. Cayambe is special. It’s a volcano that sits on the equator, you drive over it on the way to the refuge. We did two afternoons touring on the lower glacier and I had my first taste of tropical snow. Did I mention how hard everything is at the altitude? Your ultra-light touring setup starts to feel like downhill skis once you get above 5000m. I was completely wrecked after our first ski tour day on Cayambe. I learned that my frantic ‘go hard and straight up’ style of ski touring that I developed on the Kosciuszko Plateau was not suited for high altitude. I wore myself out after only a few hundred metres of vertical climbing. I watched Pablo, the local, who had been climbing at altitude with his dad since he was in his early teens. He took slow, calculated strides, carefully minimising the physical effort, whilst maximising vertical and horizontal movement. It was magical to watch. Here I was, a guy who grew up in the mountains and on skis before I could walk, taking lessons from a guy who started skiing in his late 20’s, go figure. I emulated Pablo’s stride and it worked. I found a rhythm. Breath, step, breath, step, breath. Pablo’s wealth of mountain experience shone through. We used the two days exploring the lower mountain to find a route that we could ski down. This became a common practice because, even though Pablo had been skiing on this mountain a few weeks earlier, the glaciers are so active that the skiable routes change week to week. With a route locked in, it was time we embarked on our first summit attempt. In true alpine assault style, we left at midnight, anticipating a 7 am summit. I was still suffering the effects of “gringo guts”. This affliction made the ascent harder than it should have been. My dehydration was such that I felt as if I couldn’t drink enough water, which made rationing hard. But, I pushed on, I wanted this summit. Another issue was heat regulation. Night times were freezing but day time temperatures were balmy thanks to equatorial location. OYUKI’s baselayers helped with this, while the Sencho mitt was indispensable for keeping me warm. After 7 hours of hard slogging, we arrived at the summit, jubilant and fulfilled. The view from the apex of the mountain was amazing. We got lucky and had clear skies (a trend that would continue for the rest of the trip). I got my first glimpse of the Avenida De Volcanes. To the south, in full view was Antisana (5704m), Cotopaxi (5897m) and in the distance Chimborazo (6263m). Selfies taken, high fives shared and peanut butter and jam sandwiches forced down our throats.

Our brief stint on the summit was over. It was time to descend, the fun part. The climbers who were attempting a summit on foot beat us up the mountain, an interesting fact. We were taking a different route to see if it was skiable, plus, we had all our ski gear, so it made sense they beat us up, however we definitely beat them down. It took us 25 minutes to descend (it takes 3 hours on foot). The snow quality was ok considering there hadn’t been a lot of natural snow recently. Pablo noted that, lately, it rained on these mountains with more frequency. It rarely snowed, a troubling thought. The views were incredible though. An unobstructed vista all the way to the lowlands. Masked by a thin veil of wispy clouds that blanketed the lower valleys. It was hard to concentrate on avoiding the many crevasses, holes, seracs and usual glacier fodder that dotted the slope. The combination of amazing views and pure exhaustion made sure of this. It was almost an ethereal moment. There I was, skiing down a mountain, on the equator, with a full view of the tropical jungle below. Maybe I was a little delirious from the lack of sleep. Perhaps, I was exhausted from the climb, but it was somewhat spiritual. I had done it. A huge weight lifted. I was fulfilled. Everything that was to come after on this trip would be a bonus.

Taking on Antisana (5704m)

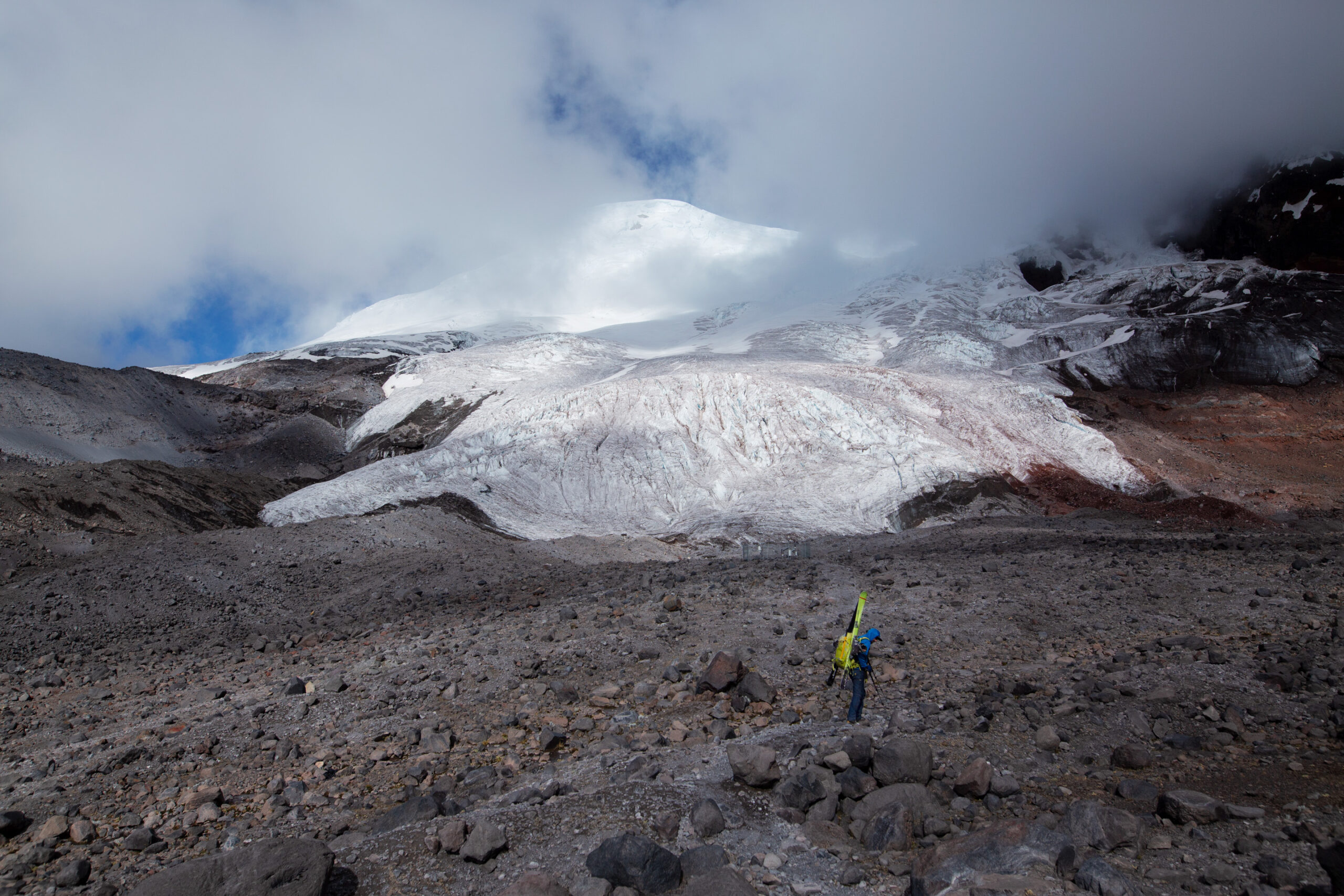

After Cayambe we headed to Antisana, the 4th highest mountain in Ecuador, though one of the most technical for climbing. This mountain is very remote and, unlike its more popular counterparts, has no refuge for climbers attempting a summit. So we set up camp. Pablo had a “glamping’ style canvas tent, a perfect all-in-one base camp solution. Anitsana challenged me. From a mental and physical standpoint, it was the real deal. The approach was a 2-hour hike at 4800m+. So that was hard enough. Once on the glacier, it was another hour to access the skiable snow. Which meant crampons on ski boots and dry glacier travel, not the easiest way up. The skiing on Antisana was good. The snow quality was better than on Cayambe. I suspect because the glacier is more active and there’s less traffic on the mountain. That, however, came with some caveats. On one of our first route finding missions, we discovered that the regular climbing route was almost impassable due to the glacier moving. A fact that no-one had alerted us to, because no-one had been on the mountain for a while. It required a traverse over a snow bridge that spanned a massive crevasse, a fall into which would result in death. We crossed, but Pablo decided it was too risky to do again, especially on a summit attempt. We spent the rest of that day finding a new route, resulting in us finding a route that went down a gap in a massive serac that formed a chute. It was super steep and rock-solid ice. Still, safer than the death fall on the other route. After finding our route we rested and set off for another summit. We left at midnight again and made our way up the mountain. This climb was challenging. We often had to swap out our skis for crampons on some sections and we were roped up for much of the climb. It involved some toe-point ice climbing, using ice axes on near vertical ice faces. At one point there was another sketchy crevasse crossing. It was dark, and I stepped onto the snow bridge with my right foot, it seemed fine. Then when I put my weight onto my right foot to move my left….the bridge gave way. I fell, straight down, into the dark abyss of the massive crevasse below. It’s hard to explain how helpless you feel when falling, even if it was for a second. I somehow had time to think, “well I’m dead” whilst also thinking “I hope the rope to Pablo stops me falling”. And “I hope I don’t pull Pablo down with me”, “Can he can rescue me if I’m still alive when I hit the ground”. Luckily, my fall was abrupt. I fell to my shoulders, caught by my skis strapped to my backpack and some weight of the rope attached to Pablo. I was dangling over a crevasse that was 100m+ to the bottom. Fortunately, I could swing my legs onto another part of the snow bridge. I managed, after five terrifying minutes, to climb up and roll back over onto the safety of the ledge. After a brief moment to catch my breath, I got up and I crossed the crevasse, far more carefully this time, and we continued. After another vertical ice wall, the final stretch was a tour along the summit ridge. We reached the summit at 7 am, then proceeded to have a very pleasant ski down. Another lesson learned on the mountain was how knackered you are after a summit. It makes the skiing hard. This isn’t a casual stroll to Kosi. You have to have your wits about you, to make sure you don’t ski into a crevasse. It was super challenging to have to be that “on” when you’re so exhausted. After some serious ski mountaineering, we made it to the bottom. Greeted by a 2-hour hike out, carrying all our gear. Worth it.

Conquering Chimborazo (6263m)

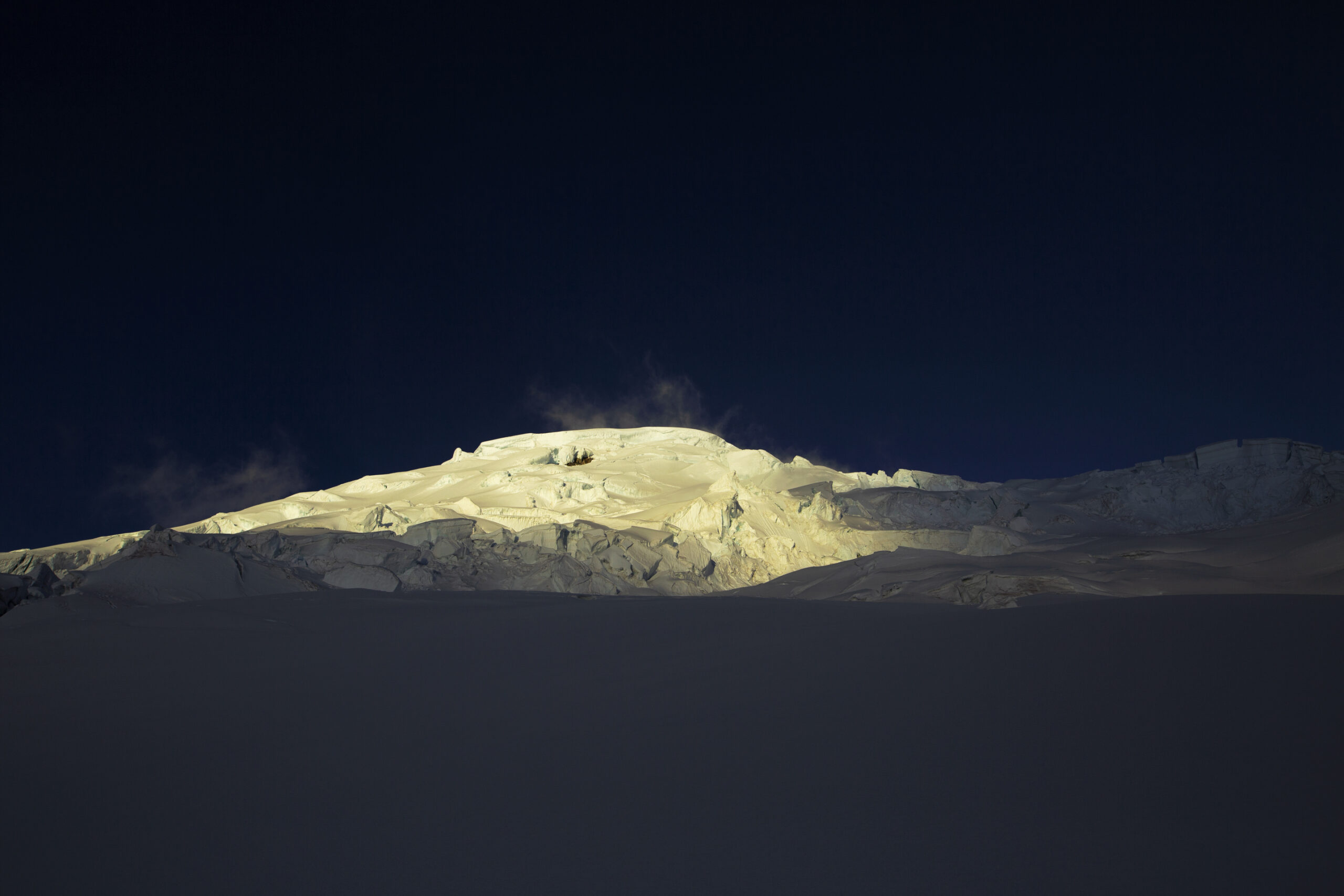

Finally, after a rest day in the town of Banos, we headed to Chimborazo, the big daddy. Taller than anything in North America, even Denali. Pablo warned me it would be hard, but I had no idea what I was in for. We didn’t do any prep ski days, because it was too hard of a climb. You have to grit your teeth and slog this one out, in one go. The current condition of the glaciers on Chimborazo mean that it’s not skiable anymore. I had been pre-warned by Pablo not to set my expectations too high. We even brought mountaineering boots, in case we were to climb it and not ski. However, we had heard rumours of fresh snow, so we planned to go for it. We arrived at the refuge to a welcome sight, there was fresh snow, all the way down to the refuge (4800m), which is rare. Adding to the excitement, as we unpacked the car, it started dumping. After a bowl of soup and a few hours of not sleeping we “woke up” at 10 pm to get ready for our summit attempt. We knew it was going to be tough and slow with all the fresh snow (up to 30cm had fallen by this point). After arming myself with my Sencho mitts and merino wool OYUKI facemask, we left at 7am to give ourselves ample time to summit. It had snowed enough to let us strap on our skis straight out of the hut, which was unheard of, lucky us. The snow kept coming down, which was tough, and it made a hard climb even harder. The ascent got arduous at about 5800m. Every step was laborious, compounded by the fresh snow making our ski cuts not hold up. We were sliding with every move, it was a “one step forward, half back” situation. Most of the climbers who were attempting a summit turned around. They passed us on the way down stating that the avalanche risk was too high to continue. Pablo and I knew the snowpack was stable, and the risk of a slide was low, so we kept going. The final push was demanding. Every step above 6000m was strenuous, like “I wanna turn around” hard. We had conceded that our ski cuts were not working. Ski touring up was becoming futile on the steep slope. The fresh snow making it nearly impossible to keep pushing through on skis. We opted to strap the skis to our backpacks and continue to the summit on foot.

At this point, my lightweight backpack felt like it was full of bricks. But, after two agonising hours, countless thoughts of turning around, groans, moans and roughly five, heavy breaths per step, at 8:00 am we finally summited. A mere nine hours and 1500m of vertical climbing later. We had reached the Veintimilla Summit which stands at 6230m. The true summit, Whymper, was another hour across the summit plateau, and only 30m higher. The 30cm of fresh snow on the summit meant that the traverse would be challenging, more so than usual. With the sun baking the snow we decided we would rather ski fresh powder than get the extra 30m. After all, we were there to ski. So, we scoffed down some food, drank some water and got ready to drop in. The view from the top was incredible, one of those moments that changes your life. Here I was, the highest I’d ever been (above sea level), looking out at a very large part of Ecuador. To my north, Cotopaxi, Antisana, and Cayambe poked through the low clouds in the valley. Delirious from the altitude, I had another epiphany. The indescribable feeling that I was experiencing, a combination of agonising pain and pure elation, mixed with complete contentment, is why people climb mountains. All the hard work, the falls, the risk, frostbitten fingers. It was all worth it when you stand on the summit. It was a surreal moment. Now for the fun part, some tropical turns. Skiing 30cm of powder? In the tropics? Now that’s something you don’t do every day. We dropped in, I made a few turns, they were good, like “good” good. I’m not going to lie though, I was completely drained. It was actually hard to ski down, even with the perfect conditions we had, but it was magical all the same. Turning and getting face shots, whilst looking down at the lowlands below was an incredible experience. One I’ll hold onto forever. After some nice turns, we navigated our way through the technical lower sections. With the sunrise, these sections had become a minefield for exposed rocks. There were “shark fins” everywhere. It wasn’t the most pleasant way to finish the climb. By this time I had a one track mind “get me to the refuge”. My legs cooked and exhausted to the point of not being able to stand. My joints aching and struggling to keep my eyes open. I was ready for a rest, a beer. Finally, we zigged and zagged our way to the trail and made it back to the hut on foot. We had done it, we had skied Chimborazo, the highest mountain in Ecuador.

It’s Time to Help

I still have unfinished business in Ecuador. I need to come back and make it that extra 30m to the Whymper summit of Chimborazo. Above all, armed with the knowledge I gained from this trip, I’m hungrier than ever to make a film about these amazing glaciers. The issue of climate change is contentious but my personal belief is that the facts are there, it’s happening, and we, as humans, are contributing. As a lifelong skier and someone who relies on snow for my livelihood, this scares me. After talking to and hearing from a lot of the locals, I’m convinced that the glaciers are receding. I overheard many stories like “we used to climb that route, now it’s impassable”. Pablo often pointed out large rocky areas that he said he had once skied. Now, scars of dirt cut through the glacier. I’m glad I had the chance to ski these magnificent mountains while it’s still possible. With any luck we’ll be able to ski in Ecuador into the foreseeable future, but the current situation provides a different story. Time will tell. In the interim, while you can’t stop the world’s emissions from entering the atmosphere all by yourself, you can raise awareness. Protect Our Winters has recently launched an Australian arm, so head to the website and see what you can do to help. I don’t want to sound like a preachy douche, but… recycle, get a reusable coffee cup, carpool, ride your bike, etc. I’m a firm believer that every little bit counts and, if everyone puts in a little bit of effort, it could add up to a large amount of positive change. Then maybe, just maybe, we can keep skiing these glaciers for years to come.